When Jasper was at school, all the dads had been in the war. Some with more cachet than others. His own dad had already been ordained as a priest and was therefore a non-combatant, much to the boy’s chagrin. He did have a story about throwing a burning mattress out of a window under heavy bombing in Sunderland, whose shipyards were a Luftwaffe target. Thinking back, it must have been pretty terrifying… running through the streets while bombs were falling, searching for people alive or dead among the burning rubble, going into houses that might crumble on top of you any moment. But it wasn’t combat, it wasn’t romantic, he didn’t fight Jerry, he didn’t have a rank… and Jasper was ashamed.

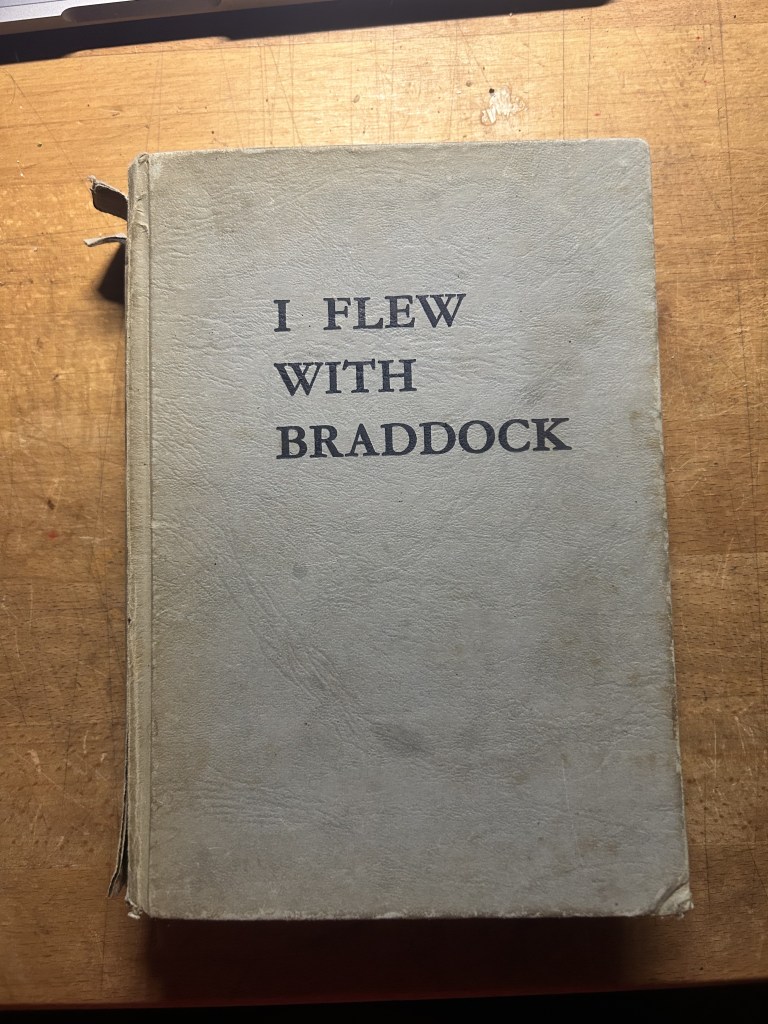

At the age of 10, young Jasper’s favourite book was ‘I Flew With Braddock’, a fictional but very realistic account of the daring exploits of Lancaster bomber pilot Sgt Matt Braddock, originally serialised in boys’ adventure comic The Rover. ‘Sergeant-Pilot Matt Braddock, VC and bar, was one of Britain’s air aces of the Second World War,’ claimed the book’s blurb, stretching the relationship between fact and fiction to breaking point. The apparent historic accuracy of the tale allowed Jasper to resist his Mother’s instructions to put the book away when at the dinner table – while his Father, detached and silent, studied some theological text at the other end – insisting it was ‘real life’. (It didn’t work.)

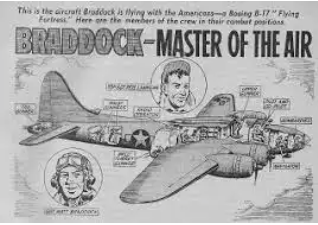

One of the unusual flavours that the author George Bourne, the notional navigator of Braddock’s Lancaster and first-person narrator, had added to the stories was that Braddock was clearly working class, from a social strata that rarely if ever commanded a crew in the wartime Royal Air Force. The accepted (quite possibly inaccurate) view of pilots was that they were predominantly public school educated, with floppy hair, neatly trimmed moustaches and upper class drawls. No-nonsense Braddock was a straight talking working man, but when at the controls – and indeed as crew chief on the ground – all the posh blokes were under his command and no quibbling.

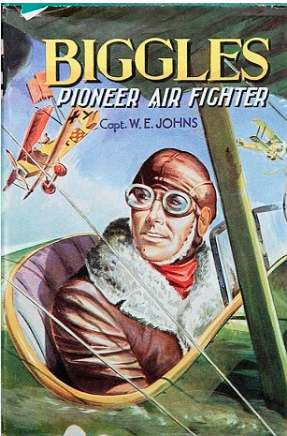

Biggles, of course, the other fictional wartime Master of the Air, was upper-middle through and through, the ‘modern day’ version of the gallant knight performing heroic acts and vanquishing the dastardly enemy – although maidens in distress were in short supply. (Ignore the 1986 sci-fi movie.) His author, Captain W.E. Johns, who churned out nearly 100 books, was himself a First World War flyer – which with, shall we say, an elastic approach to historical accuracy, was when the 17-year old Biggles first took to the air (he’d mislaid his birth certificate). He made the highly unlikely transition to Spitfires and Hurricanes in WW2, and even more improbably ended up flying the 1950s Hawker Hunter jet fighter.

The real life link to this, and an equal obsession of young Jasper’s, was ‘Reach for the Sky’, the story of double amputee Douglas Bader, Spitfire pilot extraordinaire who distinguished himself in the Battle of Britain and was immortalised in the Paul Brickhill biography and 1956 film of the same name with Kenneth More as our brave hero.

An air raid warden in a cassock wasn’t nearly good enough.